HOW MUCH ARE iPADS REALLY HELPING KIDS IN CLASSROOMS? - The drive to increase technology use in classrooms has many asking whether the investment is more fizzle than bang, and whether it’s too early to tell how wisely the money is being spent.

by R A Johnston, Education News | http://bit.ly/1j0b21P

Tuesday, February 5th, 2013 :: The drive to increase technology use in classrooms has many asking whether the investment is more fizzle than bang, and whether it’s too early to tell how wisely the money is being spent. Education author Peg Tyre has investigated the use of iPads, one of the most popular classroom additions, in TakePart. [follows] She concludes that iPads in education may offer some new teaching techniques, but by themselves, they may not be better than traditional, cheaper methods.

The classroom used to be about chalkboards, textbooks, teachers speaking directly to groups of kids, and worksheets. The iPad can take any of these roles: but in which role is it most effective?

When iPads replace textbooks, they are perhaps least effective. Downloading an e-book to an iPad does the same thing that a textbook does, but one book is probably less expensive per year than the iPad. Tyre quotes another education writer, Lee Wilson, to the effect that textbooks may be about 20% the cost of iPads, and textbooks can be used many years in a row without electronic damage.

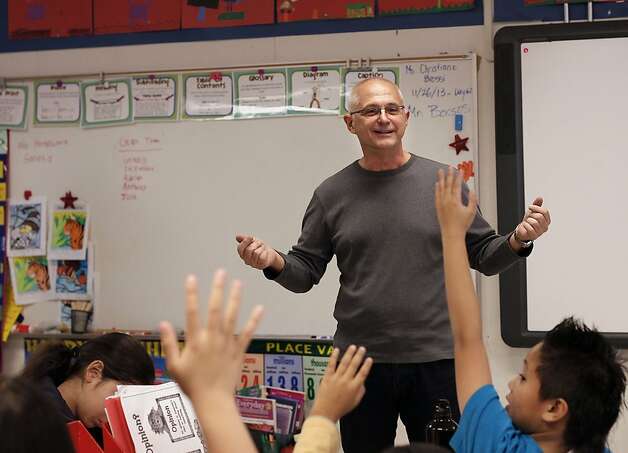

Substituting for the teacher may be among the iPad’s most effective roles. Of course, the teacher must record, upload or otherwise choose the material that the tablet presents. But once a lecture or film is on the tablet, the teacher can walk away while a group of students watches it. If the teacher only works with the students after they have learned the material presented on the iPad, she is using the “flipped learning” model in which her role is to explain, correct, and give mini-lessons as students work on projects or homework that responds to the lesson. Some schools have been using this model exclusively and can integrate technology like tablets effectively.

Tyre explains that there are other ways the iPads in schools can fill part of the teacher’s role:

Other schools, including a rapidly expanding chain of charter schools that serve low-income children, are employing what they call a “blended learning” model. It works like this: The classroom is broken down into small groups. Some kids work with a qualified, credentialed teacher, while others are shepherded to a computer room, where, under the watchful eye of a paid-by-the-hour supervisor, they zoom ahead or redo a lesson using interactive, adaptive software.

But all too often, administrators with dreams of kids using iPads in the classroom shell out thousands of dollars, only for the devices to end up not being used very much. Their capabilities are vast, but the actual materials developed for them are still limited to what’s on the market. It isn’t clear that iPads are a good use of most education dollars. At Florida’s recent educational technology conference, attendees heard about a start-up website that aims to create consumer reviews for and by teachers. EduStar hopes to allow teachers to tell how their tech devices are actually changing (or not changing) kids’ classroom experiences. Without real understanding of how a device can be used, schools can too easily fall into buying whatever is the latest fad or buzz.

Tyre reports that investment in education technology has soared in recent years.

In 2005, investors put about $13 million of venture and growth capital in the K-12 market. In 2011, venture capitalists poured $389 million into companies focused on K-12 education, according to industry analysts GSV Advisors, a Chicago-based education firm that tracks the K-12 market.

“Is it a bubble?” asks industry analyst Frank Catalano. “No, but there are signs it’s getting to be a bubble.”

Every new technology, from the radio to the early Macs and smart phones, has been touted as something that can be used to revolutionize teaching. And each generation has seen a few good changes come and go, for example as the classroom movie projector allowed students to see far more scientific and historical footage for themselves. But each generation also sees hopes rise and then be disappointed as education remains more or less the same. The jury is still out on whether iPads for education will be a success story or just another passing fad.

Are iPads and Other Classroom Gadgets Really Helping Kids Learn?

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Peg Tyre sheds light on the promise and perils of education technology.

By Peg Tyre, Take Part | http://bit.ly/1bur4PI

More teachers are bringing iPads into their classrooms, but do the tools really help kids succeed? (Photo: MCT/Getty Images)

January 31, 2013 For the last six years, the buzz about educational technology has grown deafening.

Schools across the nation are scrambling to figure out just how a new generation of technology—software and devices both in the marketplace and still to be developed—might better educate kids.

The experiments are far-reaching. Currently, there are roughly 275,000 K-12 students from 31 states who are taking classes online. School administrators all over the nation are handing out iPads and asking teachers and students to come up with new ways to learn with them. Some schools are experimenting with flipped classrooms, in which kids read or watch videos of a lecture for homework and work through problems or questions with an instructor during class time.

Other schools, including a rapidly expanding chain of charter schools that serve low-income children, are employing what they call a “blended learning” model. It works like this: The classroom is broken down into small groups. Some kids work with a qualified, credentialed teacher, while others are shepherded to a computer room, where, under the watchful eye of a paid-by-the-hour supervisor, zoom ahead or redo a lesson using interactive, adaptive software.

At another chain of charter high schools, kids sit in what resembles a call center, receive videotaped lectures and interactive lessons on a monitor, and get pulled into smaller, teacher-led groups to get a particular lesson refreshed or reinforced.

The purpose of at least some of this new technology is to make education—a sprawling, complicated enterprise—more streamlined, targeted and efficient. Rather than offer AP courses or a technical track, online classes can serve children at a small rural high school who want more enrichment, or students who find traditional academic learning not a good fit for them.

Founders of the rapidly expanding chain of Rocketship schools say when their low-income K-5th graders are fed a steady diet of computer-delivered lessons, technology “help(s) to make a child’s time in the classroom more productive because he or she will have fewer gaps preventing understanding, and Rocketship teachers will have more time to focus on extending children’s critical thinking skills.”

The idea embedded in much of the discussion about educational technology is that it can be cheaper than regular old bricks and mortar schools. Because kids spend so much time on computers, Rocketship hires fewer costly teachers per class than regular district schools. Simply equipping kids with iPads, school administrators believe, is a more cost-effective investment than spending millions on poorly written, quickly outdated textbooks.

Many teachers are embracing ed tech—blackboards and worksheets seem so last century. They are finding that using technology is altering, sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically, the way they do their jobs. Others are finding their jobs eliminated altogether. Language classes, for instance, can go from flesh and blood interactions between student and teacher to online.

All that enthusiasm among school administrators and school board members has reverberated on Wall Street, which is pouring money into the sector. In 2005, investors put about $13 million of venture and growth capital in the K-12 market. In 2011, venture capitalists poured $389 million into companies focused on K-12 education, according to industry analysts GSV Advisors, a Chicago-based education firm that tracks the K-12 market.

“Is it a bubble?” asks industry analyst Frank Catalano. “No, but there are signs it’s getting to be a bubble.”

Those who study education history called for caution as well. Every new wave of technology that has been tried in classrooms—radio, television, videocassettes, desktop computers and smartboards—has ridden a wave of enthusiasm, rapid adoption and, then, brutally dashed expectations.

“First, the promoters’ exhilaration splashes over decision makers as they purchase and deploy equipment in schools and classrooms,” said Larry Cuban, professor emeritus of education at Stanford University and author of Oversold and Underused: Computers in the Classoom in an email to me. “Then academics conduct studies to determine the effectiveness of the innovation [and find that it is] just as good as—seldom superior to—conventional instruction in conveying information and teaching skills. They also find that classroom use is less than expected…Such studies often unleash stinging rebukes of administrators and teachers for spending scarce dollars on expensive machinery that fails to display superiority over existing techniques of instruction and, even worse, is only occasionally used.” (You can buy Cuban’s excellent book here.)

Troublingly, that cycle may have already begun. Rocketship has shown that kids are learning more than their counterparts at neighborhood schools, but their blended learning model is in flux. Computer labs, once outside the classroom, are being brought into the classroom and monitored by a skilled educator. And their partnership with a tech startup, which was coming up with software to aggregate student data and help teachers plan their lessons, has ended.

|

| iPads in the classroom, too, are hardly turning out to be a panacea. Teachers in some schools use iPads to great effect. Most, not. And they are not likely to lead to cost savings. In a widely quoted blog post, Lee Wilson, tech watcher and President & CEO of PCI Education, calculated that once you consider the training, network costs, and software costs, iPads cost school districts 552 percent more than those old-school textbooks |

You can check out his blog here. But in the meantime, I’ve lifted the cool chart he made showing just how pricy iPads turn out to be. (Thanks, Mr. Wilson.)

There are signs that Wall Street’s wild enthusiasm to finance the creation of the new Model T of educational technology may be cooling. Investment dollars in the educational technology sector is down from $389 million in 2011 to $305 million in 2012.

We should all hope that the next Nikola Tesla of education technology will soon emerge. And that schools like Rocketship, which are responsible for educating so many vulnerable low-income kids, succeed in getting their model just right. Meanwhile, parents and taxpayers, be cautious. We need to make sure hype doesn’t overtake good judgment.

- Peg Tyre is the author of two bestselling books. She has written for The New York Times and The Atlantic. full bio

- TakePart is the digital division of Participant Media, the company behind important films such as An Inconvenient Truth, Waiting For Superman, Food, Inc., Good Night & Good Luck, Charlie Wilson’s War, Contagion, The Help, and many others.

smf: These two articles are almost a year old – but put into perspective, they came out at the same time as the Deasy administration’s headlong rush into the Common Core Technology Project/iPads for All implementation began. I would’ve shared them earlier with 4LAKids had I found them earlier. My bad.

A lot has changed in the almost-a-year. We’ve learned a lot. But not enough.

And the underlying premise, that parents and taxpayers – and educators – should be cautious and not be overcome by the hype has solidified. The message that the annual cost of technology-driven curriculum+instruction delivery is far higher than textbook-driven methodologies has been ignored or skipped over – put in the “parking lot” for later discussion. To be solved in later years, in future budgets – by other school boards and different superintendents. Paid for by the same taxpayers …but in other tax bills.

I am an early adopter. I want to believe that this investment in Educational Technology Infrastructure is a good idea. If spending the money will make a real difference we should spend the money. My doubt is more of the wisdom of the investor – looking for a quick-fix magic bullet – than that of the long term investment in the education of Los Angeles’ schoolchildren.

As originally proposed the LAUSD CCTP was to roll out in a single year: A one billion dollar Information Technology upgrade that would - I think/I’m not sure – be the biggest/most expensive public sector IT investment in the nation – excluding the Department of Defense and the NSA.

When LAUSD was in the peak of our building program, building 130 new schools, we were hard pressed to spend $1 billion in a year!. And,as a colleague on the Bond Oversight Committee points out: That investment created jobs in the local economy with an economic multiplier effect - and new schools that stand to last. Investing in iPads creates profits in Cupertino and jobs in Chengdu and tablets that last three years. If there’s a multiplier effect it’s a feature in the Calculator app.

That urgent rush has slowed the CCTP to a three year program. But the scope – an iPad for every student, teacher and administrator in the District – remains the same. And almost a year later – when the program was originally scheduled to be nearly complete – most of the questions aren’t just unanswered …they are unaddressed.

And finally/ironically – the second article is from Participant Media. Being a Hollywood Progressive by address+inclination I feel entitled to identify my fellow travelers. Participant brought us “An Inconvenient Truth” – but they also brought us “Waiting for Superman” (co-produced by Philip Anschutz’ ‘Walden Media – who also brought us: “Won’t Back Down”). They are capable-of+motivated-by-profit to be the propaganda arm of ®eform Inc, The Billionaire Boys Club and the Hollywood/Silicon Valley elite.

In this article they sing the praises of Rocketship Charter Schools. But even they are humming the lyric: “Slow down, you move too fast….”

Just sayin’.

Schools Seeking Results from Tech Spending

Schools Seeking Results from Tech Spending